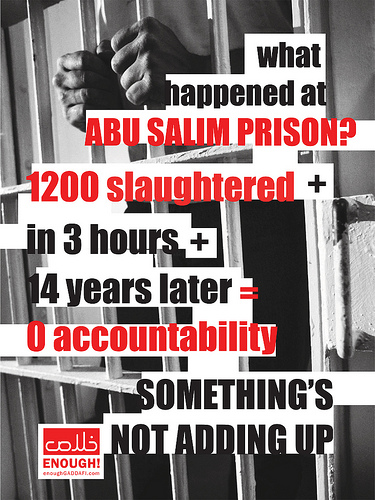

2011-02-18 The Abu Salim Massacre: Cables on Libya's Continued Impunity for 1996 Killings

Two days ahead of calls to protest the Gaddafi regime in a “Day of Rage” on February 17, members of the Committee of the Families of the Victims of the Abu Salim Massacre came out to protest. Libyan attorney and human rights activist Fathi Terbil, who represents families that had family members massacred in mass prison killings that took place at the Abu Salim prison in 1996, was arrested. Terbil’s arrest led to an eruption of protests ahead of the planned “Day of Rage.”

Protesters showed up to the police headquarters in the city of Benghazi to demand his release. The crowd outside swelled to somewhere between one and two thousand. This response demonstrated how the Gaddafi’s refusal to prosecute those responsible for the massacre of nearly 1200 prisoners in over a decade ago has created a deep resentment among Libyans toward the regime.

The arrest was an example of how the Gaddafi regime treats “regime critics” or dissidents.

Cables from Embassy Tripoli show that the massacre continues to cause political division and tension among members of the Gaddafi regime and the Libyan population. It also shows that the site of the brutal massacre has become the home of former Guantanamo Bay detainees.

Cables from Embassy Tripoli show that the massacre continues to cause political division and tension among members of the Gaddafi regime and the Libyan population. It also shows that the site of the brutal massacre has become the home of former Guantanamo Bay detainees.

In December 2009, HRW released a report titled, “Truth and Justice Can’t Wait.” A cable details what happened when the organization held an “unprecedented public forum for discussion of Libya's past abuses,” the “first such launch in-country.” The Gaddafi Development Foundation, at great risk, helped facilitate the forum. “Members of the Libyan and international press together with relatives of past victims of Libyan human rights abuses -- and members of Libya's powerful security forces” came together to discuss the report.

Five families, according to the cable, were detained on their way from Benghazi to the event. Visas for Washington Post and New York Times journalists seeking to attend the press conference were denied. And, what unfolded at the event is described as follows:

4.(C) The short briefing and recommendations were followed by a lively question-and-answer segment that quickly degenerated into a litany of grievances against the Internal Security Organization (ISO) for years of repression. A family member of a victim of the Abu Salim riot, holding a photo of his dead brother, described his brother's case in detail claiming the family had taken food and clothing to the prison for 13 years, until they received a death certificate this spring that lacked a cause of death. A woman from Benghazi asked whether HRW would apply pressure on the Government of Libya (GOL) to prosecute the director of an orphanage accused of sexually abusing girls under his care. Journalists and security agents swarmed those who spoke, some of whom were flanked by known employees of the QDF.

5.(C) After several longer testimonies, a journalist from state news agency JANA spoke, claiming to have accepted government compensation for his brother's death at Abu Salim. He railed against HRW and those continuing to petition the government for justice on past abuses as "anti-Libyan" and denounced HRW for holding Libya to different standards than the rest of the world. He asked how HRW's report could even be written when abuses like "the war in Iraq, Abu Ghraib, and Guantanamo" went unpunished. He defended Libya's actions as necessary to keep the country safe, and noted that no attacks like 9/11 could occur on Libyan soil due to these protections. HRW reiterated its non-governmental and politically neutral status, and pointed out that it had been the first organization to report on alleged abuses at Abu Ghraib. While HRW's explanation appeared to calm some in the audience, his statements ended what appeared to be a carefully scripted piece of theater. The next speakers, only some of whom seemed to be at the event at the invitation of the QDF, made more vocal complaints on the deaths or disappearances of relatives and made specific claims against the ISO.

6.(C) The event quickly evolved into an angry shouting match between government supporters and a sizable group of Libyan citizens urging the creation of compensation and truth commissions. The pro-government crowd, taunted by members of the audience as ISO agents, verbally attacked the HRW and their detractors, causing several individuals from both sides to storm out. After this public catharsis had endured for over 90 minutes and with no further questions about the content of the report, HRW ended the press conference and spoke individually with several government critics. (Notably, the actual events differed from a Times of London report, which exaggerated the details of the role of GOL security officials in "shutting down" the press conference.) Watching from the parking lot, emboffs [embassy officials] observed several of the most vocal government critics entering a large van with staff from the QDF unhindered by security agents. Others, including a lawyer claiming to have represented Idriss Bufayed, departed individually without apparent incident.

Months earlier, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi established a human rights organization, “the Arab Alliance for Democracy, Development and Human Rights, whose mandate would consist of tracking human rights abuses in the Middle East.” It was upon the establishment of this organization that, according to a March 2009 cable, Gaddafi’s son invited HRW to visit Libya and educate him on how to run an “effective” human rights organization. And, subsequently, HRW put together the report presented at the December 2009 forum.

The December 2009 HRW report lauds the “unprecedented activism” of the families, who have in the face of state repression, fought for truth and justice. It notes the Committee did not form until April 2008. The formation defied Libyan laws that “severely restrict freedom of assembly and association.” The Committee tried to register as a non-governmental organization (NGO) with the Internal Security (incidentally, the establishment responsible for the impunity so far). The Internal Security refused to let the Committee register.

The Committee began to hold public demonstrations in Benghazi in June 2008 “at high risk since demonstrations are prohibited in Libya.” Somewhere between thirty to one hundred and fifty individuals showed up to demonstrations. Human Rights Watch quoted one family member who told of the intimidation and how “more active members” were being “summoned for interrogation” and at demonstrations “security forces turn out in force, they are filming all the family members who turn up. Senior security officials come to the demos and tell the older members to go home.”

Human Rights Watch (HRW) has published a legacy report on the massacre, which resulted in the death of around 1200 prisoners. Libyans and those following events on Libya have been circulating the report to help provide context to events that are unfolding.

For those unfamiliar, here is an excerpt from the report that provides details on the massacre:

According to al-Shafa’i, the incident began around 4:40 p.m. on June 28, when prisoners in Block 4 seized a guard named Omar who was bringing their food. Hundreds of prisoners from blocks 3, 5 and 6 escaped their cells. They were angry over restricted family visits and poor living conditions, which had deteriorated after some prisoners escaped the previous year. Al-Shafa’i told Human Rights Watch:

Five or seven minutes after it started, the guards on the roofs shot at the prisoners—shot at the prisoners who were in the open areas. There were 16 or 17 injured by bullets. The first to die was Mahmoud al-Mesiri. The prisoners took two guards hostage.

Half an hour later, al-Shafa’i said, two top security officials, Abdallah Sanussi, who is married to the sister of al-Gaddafi’s wife, and Nasr al-Mabrouk arrived in a dark green Audi with a contingent of security personnel. Sanussi ordered the shooting to stop and told the prisoners to appoint four representatives for negotiations. The prisoners chose Muhammad al-Juweili, Muhammad Ghlayou, Miftah al-Dawadi, and Muhammad Bosadra.

According to al-Shafa’i, who said he observed and overheard the negotiations from the kitchen, the prisoners asked al-Sanussi for clean clothes, outside recreation, better medical care, family visits, and the right to have their cases heard before a court; many of the prisoners were in prison without trial. Al-Sanussi said he would address the physical conditions, but the prisoners had to return to their cells and release the two hostages. The prisoners agreed and released one guard named Atiya, but the guard Omar had died.

Security personnel took the bodies of those killed and sent the wounded for medical care. About 120 other sick prisoners boarded three buses, ostensibly to go to the hospital.

According to al-Shafa’i, he saw the buses take the prisoners to the back of the prison.

Around 5:00 a.m. on June 29, security forces moved some of the prisoners between the civilian and military sections of the prison. By 9:00 a.m. they had forced hundreds of prisoners from blocks 1, 3, 4, 5 and 6 into different courtyards. They moved the low security prisoners in block 2 to the military section and kept the prisoners in blocks 7 and 8, with individual cells, inside.

Al-Shafa’i, who was behind the administration building with other kitchen workers at the time, told Human Rights Watch what happened next:

At 11:00, a grenade was thrown into one of the courtyards. I did not see who threw it but I am sure it was a grenade. I heard an explosion and right after a constant shooting started from heavy weapons and Kalashnikovs from the top of the roofs. The shooting continued from 11:00 until 1:35.

He continued:

I could not see the dead prisoners who were shot, but I could see those who were shooting. They were a special unit and wearing khaki military hats. Six were using Kalashnikovs.

I saw them—at least six men—on the roofs of the cellblocks. They were wearing beige khaki uniforms with green bandanas, a turban-like thing.

Around 2:00 p.m. the forces used pistols to “finish off those who were not dead.

Around 11 am the next day, June 30, security forces removed the bodies with wheelbarrows. They threw the bodies into trenches—2 to 3 meters deep, one meter wide and about 100 meters long—that had been dug for a new wall. “I was asked by the prison guards to wash the watches that were taken from the bodies of the dead prisoners and were covered in blood,” al-Shafai’i said.

One family member of an Abu Salim prisoner who died in the incident told Human Rights Watch that a former prisoner who had been in a different section of the prison at the time told him that:

He and others went into the cells of the men who had refused to move. He said they found hair and skin and blood of people splattered on the walls. They saw the piece of a jaw of one man on the floor. Even though they had cleaned up the bodies, they didn’t do a good job, so there were still remnants on the walls and floors.[123]

The killing of 1200 prisoners at Abu Salim amounts to a violation of the right to life, in Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICPPR) and a fundamental principle of international law accepted by the international community. It may also amount to a crime against humanity, one of the most serious of crimes in international law.[124]

The Gaddafi regime's security apparatus, under the direction of the US, has been hosting the US’ Guantanamo Bay detainees in the Abu Salim prison. An excerpt from a June 2008 cable reports detainees have described the prison as much worse than the prisons run by Libya’s External Security Organization (ESO), which they were held in when arriving in Libya:

(S/NF) In the course of a meeting on June 10 separate issues (reftel), two detainees returned from Guantanamo Bay expressed to P/E Chief the fact that detention facilities run by Libya's External Security Organization (ESO) were markedly better than the Abu Salim prison. ISN 194 and ISN 557 were held at an ESO detention facility for approximately three months after their return to Libya in December 2006 and August 2007, respectively. Both were then transferred to the Abu Salim prison, which is located in the suburbs of Tripoli.

A security official who accompanied P/E Chief during his visit explained that Abu Salim is controlled and managed by military police; it is the facility at which terrorists, extremists and other individuals deemed to be particularly dangerous to state security are detained. Depending on the nature of their case, such individuals may be questioned by ESO before being transferred to the custody of the Internal Security Organization (ISO) for further questioning. While military police officials formally manage and guard Abu Salim prison, ISO officials play a large role in management of the facility because they bear primary responsibility for many of the prisoners there.

The detainees claim they are given less opportunities to exercise at Abu Salim than they had at the ESO facility. They assert that the food was better and the guards and officials treated them better at the ESO facility. They say they were given access to books, radio and television but not at Abu Salim. And, at the ESO facility, it was not dark, dank and in poor condition like Abu Salim.

The cable suggests the conditions have been “dramatically improved” since ESO Director Musa Kusa took control in 1994 because Kusa, “disturbed by consistent reports of inhumane treatment in ESO detention facilities, issued orders in 1996 directing that his officers immediately cease the abuse of detainees in their custody. The “casual abuse” of detainees was allegedly stopped.

A security official presumably working with the detention facilities in some capacity says the detainees “desire to return from Abu Salim prison to the ESO facility” are “typical of detainees who are transferred from the custody of ESO to Abu Salim.”

The previously mentioned cable on Gaddafi’s son starting a human rights organization features this comment from a US diplomat at the end:

Human rights remains one of the most sensitive issues in Libya, particularly for conservative regime elements, many of whom personally played a part in the most serious transgressions of the late 1970's and 1980's. Most human rights initiatives backed by Saif al-Islam and the QDF (the Bulgarian nurses, families of victims of the 1996 Abu Salim prison massacre, the release of former Libyan Islamic Fighting Group members) have downplayed personal responsibility and focused on compensation as a means to resolve old grievances. Identifying and seeking to hold accountable specific individuals would be a significant evolution.”

Abu Salim is Libya's Abu Ghraib, a prison which the US has found useful because it's a place to relocate Guantanamo detainees.

Unfortunately, for the families of those killed in the Abu Salim prison massacre, the US has done little more than identify that Libya has a problem with upholding human rights. It has given rhetorical support to human rights organizations like Amnesty International and HRW. But, the need to maintain post-9/11 anti-terrorism efforts have led the US to keep a distance virtually ensuring impunity for those who were responsible for the Abu Salim massacre.

And now, failure to confront the human rights problem in Libya (and US human rights problems) is partly why the protests in Libya have the potential to grow.

Photo by EnoughGaddafi